You may have seen it play out before: A star performer is promoted to lead a team of peers but struggles to get the most out of them. In fact, you may be (or have been) that leader. This experience is surprisingly common in organizations of all sizes and across professions. The new leader thinks, “I’ll lead by example. I’ll show them how hard I work and that will inspire them to work just as hard.” That logic, however, is flawed.

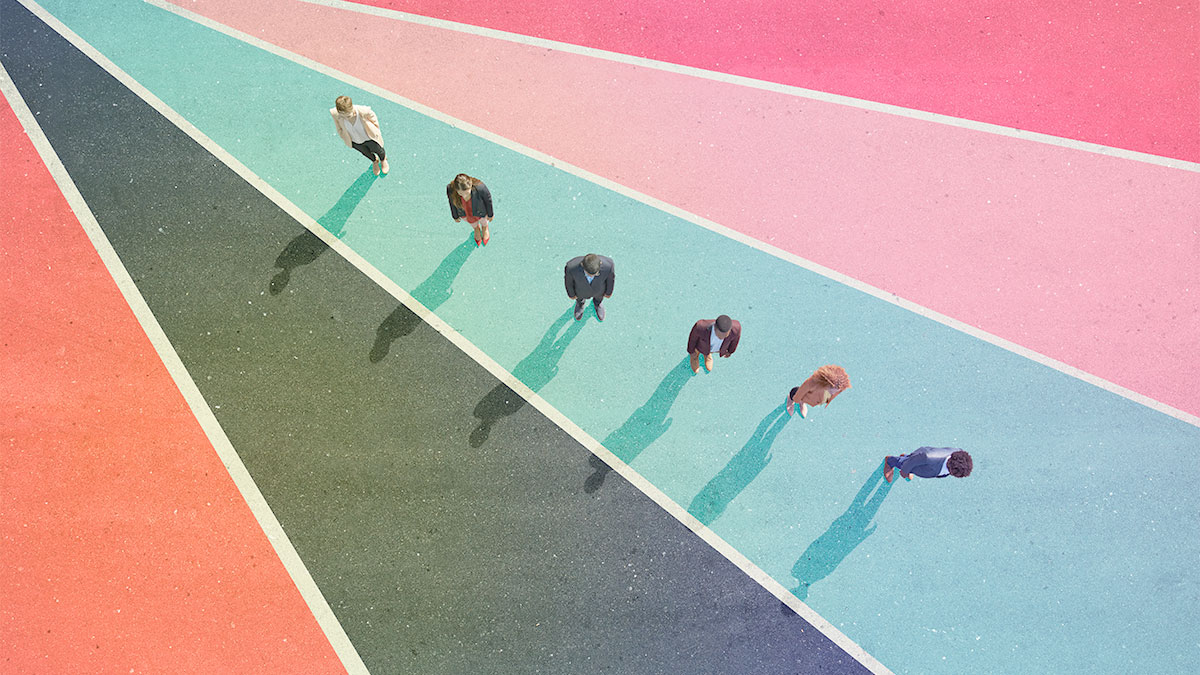

Psychologist Daniel Goleman has referred to this style of leadership as “pacesetting.” It happens when the leader sets a high bar for performance and works hard (and often long hours) to raise expectations for the rest of the team. The leader runs like a pacer in a race, but runs faster than everyone else, hoping to inspire them to catch up. While a few team members can temporarily keep up, the rest slow down or push back, and the team’s performance starts to deteriorate.

The gap between what the leader is trying to accomplish and what’s actually achieved is often due to a mismatch in sources of motivation. The leader likely has an innate competitive drive and a strong focus on career goals. The team members probably have different motives that stem from their own ambitions, values, and individual goals, which are often different from the leader’s.

As someone new to leadership, it can be easy to rely on pacesetting. You were likely promoted into your role due to your outstanding performance as an individual contributor, and now you want to hold other people to that same standard. But, as Goleman notes, pacesetting tends to erode trust and drive a wedge between managers and their teams.

When you aren’t on the same page as your subordinates, several bad habits can start to sneak in. You may hesitate to delegate tasks because no one can meet your expectations. In fact, you may be tempted to take over some of you team’s responsibilities since they don’t have the same sense of urgency as you. You may become visibly frustrated with people and have lots of corrective feedback. You may even begin to divide important tasks and projects between the one or two team members you can trust (and who are likely “the runners” trying to “keep pace” with you).

While I don’t suggest that young and ambitious leaders completely water down their high standards, if you want to get the most out of your team, it’s important to recognize that each person has their own motives. Slowing down to learn those motives can help you find more effective ways to encourage each person to do their best work.

What Motivates Your Team?

Unfortunately, learning what motivates other people is not as straightforward as directly asking someone, “What motivates you?” Most of us struggle to articulate our actual motives and may not be fully conscious of them. A better approach, and one I’ve coached many leaders to take, involves asking three powerful questions focused on the past, the present, and the future.

The following questions can help you uncover how your team members relate to their work and what lies at the root of their ambitions.

1) Look backward: What have you accomplished?

The first question I ask my clients to ask is, “What have you accomplished in the last four to six months that makes you most proud?” I tell them to follow that question with, “What about that work makes you proud?”

The first answer gives them insight into the kind of work their team members like to do and the second tells them what about that work makes them feel motivated.

When you ask these question to your own team, they key is to listen for hints of intrinsic motivation — or the incentive we feel to complete a task just because we find it engaging or enjoyable. For example, if your team member answers the first question and says they’re proud of writing a viral social media post simply because they really love that kind of work, they were likely intrinsically motivated by it. Now, your job is to find out why.

There are a few components that drive intrinsic motivation: competence, autonomy, and connectedness, according to the theory of self-determination (STD). Let’s take a closer look at each:

Competence: If your team member says they find social media writing rewarding because it comes naturally to them and they find it validating when other people share their content, they may be motivated by work that makes them feel competent. STD postulates that the satisfaction we feel when we overcome a challenge and perform well makes us feel more competent, which then leads us to feel intrinsically motivated.

Autonomy: If your team member is proud because they wrote the post in their own way without the guidance of anyone else, they likely value and are driven by the feeling autonomy. In fact, psychologists have found that competency and autonomy often play off of each other.

Connectedness: If your team member is proud because they collaborated well with others to write the post and saw it resonate widely, they may be motivated by connectedness. This means the task itself wasn’t as motivating as being part of a group that accomplished it together, providing a sense of belonging.

Finally, you may hear about what accomplishing the task meant to your team member. Though this isn’t included in STD, many of us are motivated by work that is meaningful and has a purpose.

As you listen to the answers, make note of what made your team member proud (competency, autonomy, connectedness, and/or purpose). Start to think about what responsibilities align best with those sources of motivation. For instance, if your team member described how they worked as part of a team (connectedness) to solve an important problem (purpose), you might think about other projects you could assign them to feed these internal drives.

2) Look at today: What is getting in the way?

The second question can help surface demotivators, or things that are frustrating your team and sapping their motivation. A big part of your job as a leader is to remove the barriers blocking their potential. Beyond that, this question will give your people an opportunity to feel heard and appreciated.

Some leaders are afraid to ask about barriers for fear of surfacing things they can’t change (hard deadlines or limited resources). Others worry that the conversation will devolve into a complaining session. To move past these fears, remind yourself that not every roadblock can or needs to be solved — listening and caring can be enough. Showing empathy and being open to looking for ways to compensate or work around a roadblock can go a long way and even help unblock your team member for the time being.

When your team member shares their frustrations, ask, “What do you think we can do about that?” (Depending on the issue, you might substitute “we” with “your” or “I.”) If the issue is truly unsolvable, discuss how your team member can still be effective given the constraint. Even if the solution isn’t obvious, you’re still building a foundation of trust, connecting, and surfacing a frustrating problem. You’ll gain information that can help you prevent similar barriers in the future.

3) Look forward: What would you like to do more of?

The final question opens the door to what your team member would like more of going forward. There may be things they want but have never communicated to you — either because they couldn’t find the right time or felt they needed permission to ask.

One team member may want to learn a new skill while another wants to tackle a challenging project. One team member may want to participate in a mentoring program while another wants to gain experience in a different department.

As a leader, you don’t have to fulfill every request, but asking the question will help you figure out how to make their jobs more interesting and motivating. It will create some room for “job crafting,” which involves making small changes to better fit the role to the individual.

How and When Should You Ask These Questions?

Each above question has the potential to yield powerful insights, but you need to be conscious of when and how you hold the conversation to see them. Here are a few tips:

Time it right.

While these questions might feel like a natural fit for your annual performance evaluations, I would advise asking them sooner. The end of the year is not the time to make amends for lost motivation.

Motivating your team and keeping their morale high is part of your daily job. That’s why I recommend asking these questions during a regularly scheduled one-on-one meeting and make them the entire focus. This will give you the space you need to have a meaningful conversation and start making changes sooner than later.

Give your team member a heads up.

Don’t ask your team member these questions on the spot. To get the most thoughtful answers, they’ll likely need some time to reflect and prepare. Consider sending the questions via email in advance of your meeting.

You might say, “In preparation of our meeting this week, I wanted you to ponder on three questions. Not only will these help you reflect on your work and your future goals, but your responses will also help me plan for your growth and development.”

Don’t make it a one-time thing.

You should be having this conversation about every six to 12 months. It’s a good way to check in with your people on something besides what they are working on right now. You can also use each subsequent meeting to get feedback on any changes that have come about since your last discussion. Be sure to listen actively, take notes, and repeat back any major points your team member makes to show that you’re paying attention.

. . .

The ultimate goal is to make your team members feel heard and cared for while uncovering their deepest motives. If you approach these discussions with a curious mindset and make them a regular practice, you will find them paying dividends in the form of team cohesiveness, productivity, and morale.